Africa’s Agribusiness Transformation Will Be Built by Markets, Not Aid

For decades, Africa’s agribusiness narrative has been dominated by discussions around food aid, productivity gaps, and smallholder vulnerability. While these challenges are real, they often obscure a deeper structural issue that continues to limit the continent’s agricultural potential: the absence of strong, reliable market institutions. According to Bharat Kulkarni, an independent consultant specialising in African agribusiness and commodity markets, Africa does not suffer from a lack of production alone—it suffers from weak market architecture.

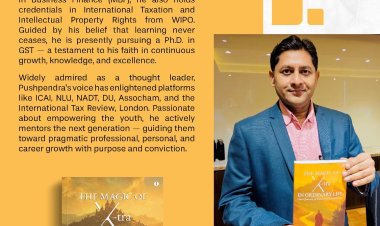

Having worked hands-on in building commodity exchanges and structured markets across Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Malawi, Ghana, Tanzania, and Nigeria, Kulkarni brings an operational perspective rarely found in policy debates. His book, African Agribusiness, positions market institutions—not subsidies or short-term interventions—as the foundation of sustainable agricultural growth.

At the heart of the problem lies the fragmentation of agricultural markets. Farmers often sell produce without transparent price discovery, quality standards, or assured settlement mechanisms. This erodes trust, discourages private investment, and traps producers in cycles of low income and high risk. Structured markets, such as commodity exchanges supported by Warehouse Receipt Systems (WRS), address these gaps by formalising trade, enabling access to finance, and integrating farmers into larger value chains.

One of the most powerful examples comes from the Ethiopia Commodity Exchange (ECX), where Kulkarni served as UNDP-deputed Head of Trading Operations. The ECX transformed Ethiopia’s coffee sector by introducing standardised grading, transparent auctions, and guaranteed payments. Farmers gained better price realisation, exporters benefited from consistent quality, and the overall market became more resilient. The lesson was clear: when institutions work, trust follows—and with trust comes scale.

Yet, many agribusiness reforms fail because they attempt to replicate global models without adapting them to local realities. Kulkarni’s experience in Malawi and Rwanda demonstrates that diversification away from single-crop dependence—such as tobacco—requires more than policy intent. It demands coordinated investments in storage, logistics, market access, and finance. Without these elements, even well-designed reforms struggle to gain traction.

A key argument in African Agribusiness is that Africa’s perceived investment risk is often misunderstood. Risk is not inherent to African agriculture; it is created by institutional voids. When pricing is opaque, contracts are weak, and post-harvest systems are unreliable, capital naturally hesitates. Strengthening market infrastructure reduces uncertainty and unlocks both domestic and international investment.

Kulkarni also highlights the relevance of India’s agribusiness journey. India’s experience with regulated markets, commodity exchanges, and agri-finance offers valuable lessons for Africa—particularly in balancing farmer inclusion with market efficiency. This India–Africa comparative lens forms a central pillar of his thought leadership, reinforcing the importance of South–South cooperation in a rapidly changing global food system.

As climate change, supply chain disruptions, and food security concerns intensify, Africa’s ability to build resilient agribusiness systems will depend on long-term institutional thinking. African Agribusiness challenges policymakers, investors, and development agencies to move beyond aid-led narratives and focus on market-led solutions that endure.

For those seeking a grounded, insider perspective on what truly drives agricultural transformation in Africa, this book—and its author—offer insights shaped not by theory, but by experience.